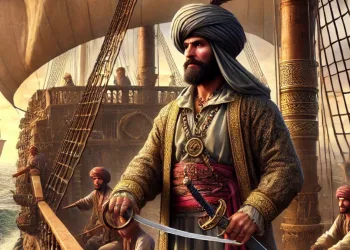

ʿAbbās Abū al-Qāsim ibn Firnās (عَبَّاس بن فِرْنَاس) was a 9th-century Andalusian polymath, born around 810 CE in Izn-Rand Onda, in what is now southern Spain, and is best known for his attempts at human flight; one of the earliest in recorded history.

He lived during the Umayyad Emirate of al-Andalus, a golden age characterized by a brilliant flourishing of arts and sciences, and the ‘convivencia’ of religious harmony and coexistence.

Little is known about Ibn Firnas’ childhood and early life but it’s understood he was of Amazigh (Berber) descent or perhaps a native of the Iberian Peninsula who adopted Islam.

In the 9th century, Córdoba was the intellectual and political capital of al-Andalus. It’s where anyone interested in science, poetry or scholarship eventually went; in the same way students today go to major universities, which are sometimes thousands of miles away.

So while Ibn Firnas was from Izn-Rand Onda, it’s very likely that he moved to Córdoba as a young man to study and later work at court.

As a young man of talent, he probably studied in the great libraries and mosque-schools of Córdoba, where disciplines like Arabic grammar, poetry, Qurʾanic studies, mathematics and astronomy were taught. He also likely came into contact with the translation movement from the East — Arabic versions of Greek scientific texts from thinkers such as Ptolemy, Aristotle and Galen.

By virtue of his talents, Ibn Firnas eventually rose to become a central figure of the Umayyad court of Córdoba, where Emir ʿAbd al-Raḥmān II (r. 822–852) actively fostered the cultural flowering of al-Andalus.

This was the perfect environment for Ibn Firnas’ genius to flourish. He proceeded to become an inventor, scientist, engineer, poet, musician and astronomer.

Some of his achievements include:

– Devising a local method for manufacturing or working with transparent glass, which advanced glassmaking in Al-Andalus and reduced the region’s reliance on imports.

– Building a planetarium in Córdoba that simulated the motions of the planets and stars, an early attempt at a mechanically articulated model of the cosmos.

– Reportedly building a mechanical time-keeping device that could be applied to musical performance.

While Ibn Firnas had many talents, he is most well known for his attempts at human flight.

In 852, his first attempt was less about sustained flight than it was about surviving a descent. There was no complex machine; just a large, loose cloak that was stiffened with wooden struts, creating a wide wing-like surface.

In front of a large crowd, he climbed to the top of the minaret of the Great Mosque of Córdoba, one of the highest points in the city, and leaped.

The cloak didn’t allow him to fly, but it acted as a highly effective primitive parachute. It caught the air, slowing his descent enough so that his rough landing caused only minor injuries.

He walked away from the experiment, considered one of the earliest documented, partially successful parachute descents in history, with a lot to think about. For Ibn Firnas, it was evidence that a human could have some control in the air using a manufactured device.

It’s important here to point out that this leap from the Great Mosque of Córdoba has been attributed to an individual named Armen Firman, not Ibn Firnas. Some sources suggest that Ibn Firnas witnessed this event, which inspired him to try his hand at flight.

Other sources leave out this leap altogether, suggesting that perhaps Ibn Firnas had only one attempt at flight, and historical embellishment created two separate instances.

And another explanation is that Armen Firman is simply a latinized version of Ibn Firnas’ name, and that he did indeed jump from the Great Mosque in 852.

Whichever version we go with, it’s understood that Ibn Firnas made an attempt at sustained flight in 875 using some sort of ornithopter; a rigid frame covered in silk and attached with eagle feathers. It acted as a type of glider on which the large wings could be manipulated by his arms.

On Jabal al-ʿArūs, a hill outside the city of Córdoba, Ibn Firnas, now aged around 65 to 70 years old, gathered a large crowd to witness the event.

Legend has it that he explained his plan to the crowd: “Presently, I shall take leave of you. By guiding these wings up and down, I should ascend like the birds. If all goes well, after soaring for a time I should be able to return safely to your side.”

Legend goes on to say that Ibn Firnas launched himself into the air, successfully gliding and flapping for as long as ten minutes. He reportedly “flew a considerable distance, as if he had been a bird.”

The landing, however, resulted in a crash and serious injuries to his back. He lated realised that birds use their tails not just for steering, but as a stabilizer and brake for landing; something his ornithopter was lacking.

Ibn Firnas’ injuries prevented him from building a third, improved model with a tail. One can only speculate what he could have achieved with another attempt, but his legacy lives on.

He is widely celebrated as the founding father of aviation; the first person in history to design, build and test a flying machine that carried a human through the air. His sustained flight in the 9th century was a milestone that wouldn’t be replicated for centuries.

13th century English polymath and one of the earliest European advocates of the modern scientific method, Roger Bacon, heavily studied and was influenced by Arabic texts that had begun to circulate in Europe during the 13th century.

In his “Letter on the Secret Works of Art and Nature”, written around 1256–1260, he may have been influenced by Ibn Firnas, writing, “It is possible to make a machine by which a man may fly, in which the man, sitting in the middle, and turning some kind of engine, may cause artificial wings to beat the air after the manner of a bird in flight.”

Ibn Firnas’ legend would span centuries and transcend borders.

17th-century Ottoman chronicler Evliya Çelebi, writes about Hezârfen Ahmed Çelebi, an intellectual or experimenter who attached wings to his arms and flew from the top of the Galata Tower and passed across the Bosphorus. One can’t help but notice the similarities with Ibn Firnas’ flight 750 years earlier.

Today, there’s a statue of Ibn Firnas with wings attached to his outstretched arms at Baghdad International Airport. There’s an 89 km wide crater on the Moon named after him. And Puente Abbás Ibn Firnás is a bridge connecting the banks of the Guadalquivir River in in Córdoba, Spain.

Ibn Firnas was a product and a symbol of the Islamic Golden Age. He embodied the ‘scientific method’ long before it was formally defined in Europe, and his legacy lives on as a foundational figure in the history of experimental science.