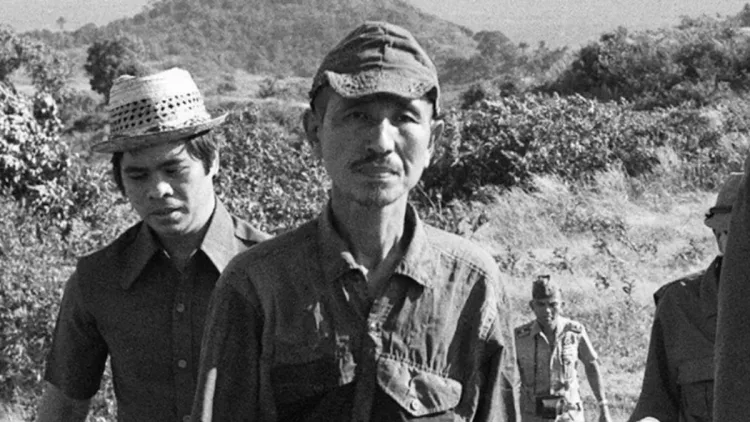

Hiroo Onoda was a Japanese intelligence officer born in 1922 who became famous for refusing to believe WW2 had ended, continuing to fight for the Empire of Japan nearly 29 years after its surrender in 1945. He remained hidden in the jungles of Lubang Island in the Philippines, conducting guerrilla warfare and evading capture until he finally surrendered in 1974.

When Onoda finally resurfaced from his hiding spots in 1974 and engaged with those sent to find him, he estimated his biological age to be 37 or 38. He was in fact 51 years old and felt that he could have held on for at least another 20 years.

What made Hiroo Onoda stay on Lubang for so many years despite clear signs, shown over and over, that the war had ended? What could push someone to keep going; a feat almost unfathomable to the generation in the 1970s, and to the generation of today?

To understand, we need to travel back to the society in which Hiroo Onoda was born and grew up.

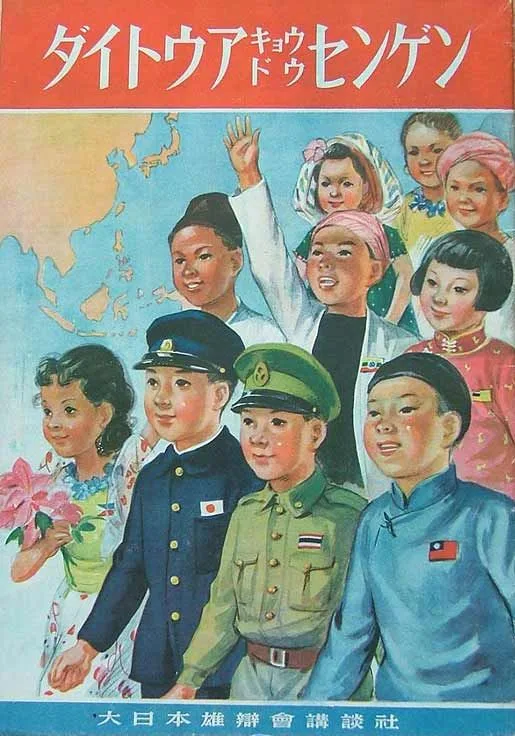

Onoda was born in 1922 is what today is the Japanese city of Kainan. At a time when Western colonialism had been running rampant in the 17th and 18th centuries, Japan was experiencing a 200 year period of peace and prosperity, managing to fend off foreign invasion attempts until an aggressive mid-1800 visit from the US Navy.

This shock, which threatened Japan with obliteration unless it opened up its economy to trade, forced Japan to build up its military strength and technological capabilities over the next few decades. As Japan stepped up its industrialisation, its aspirations shifted from defense to territorial acquisition.

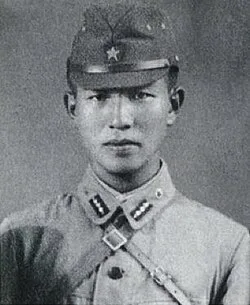

It was in this era of Japanese overseas expansion that Hiroo Onoda grew up. He spent some time in Hankow, China, which was then under Japanese occupation and when the United States declared war on the Empire of Japan in 1941, Onoda was inducted into the Japanese Imperial Army the following year.

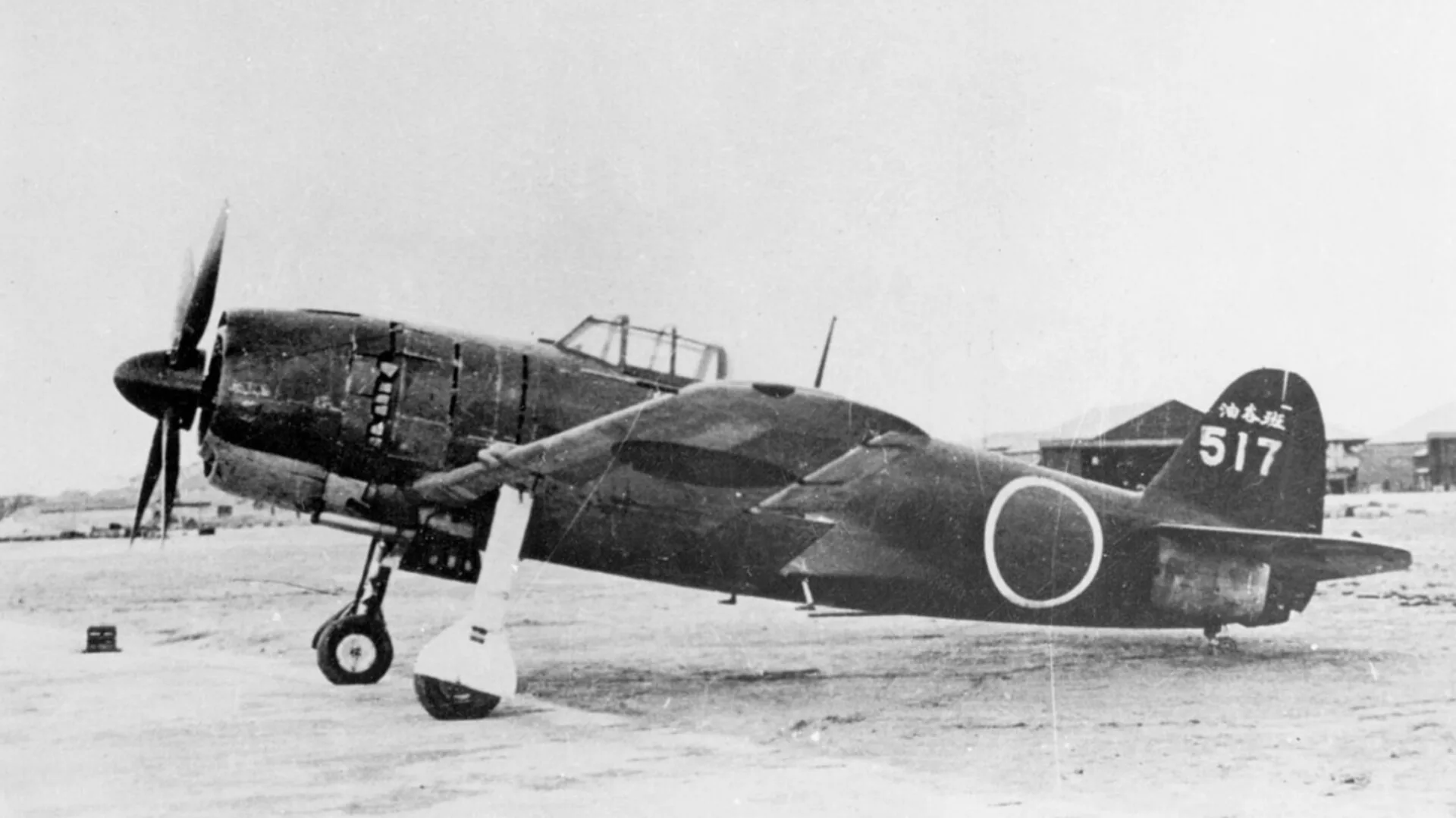

In 1944, when the war situation for Japan was getting desperate, he was trained in secret warfare and was ordered to lead a garrison in guerrilla warfare on Lubang Island in the Philippines.

Japanese citizens during the period Onoda grew up in were taught to have unyielding loyalty to the Empire and Emperor. It was a source of great shame to have surrendered to the enemy during the wartime years. Instead, fighting to the death was the honourable thing to do.

By the time Onoda was deployed on Lubang, there was widespread understanding that an invasion of mainland Japan by the Allies was only a matter of time. But despite territorial losses and a deteriorating war machine, many people in Japan had the belief that eventually things would turn around and they’d be victorious.

Unlike the cautious and realistic Japanese leaders of the mid 1800s, those of the 1930s and early 1940s were convinced of the Empire’s invincibility. To them, each Japanese citizen would fight for the Empire and the only way Japan would lose was if every Japanese individual were killed.

Hiroo Onoda was imbued with this mentality. But contrary to the societal expectation of giving up your life for the Emperor, a senior officer had once told him, “You are absolutely forbidden to die by your own hand. It may take three years, it may take five, but whatever happens, we’ll come back for you.”

In late February 1944, when Allied forces landed on Lubang, organised Japanese military formations were quickly wiped out, until only 4 people made up the totality of Japanese forces.

To survive, Onoda moved from one place to another, hunted for food and kept his alertness high in case of an attack or capture attempt. He held a belief that eventually Japanese reinforcements would be sent to Lubang to retake the island.

Other Japanese troops remaining on Lubang were Private First Class Akatsu, Private First Class Kozuka and Corporal Shimada. Akatsu would desert in 1949, leaving Onoda to form a deep bond with Kozuka and Shimada over the years that followed.

When Japan signed the Instrument of Surrender on 2nd September 1945, following the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki the month prior, Onoda was convinced that Japan was still at war. Any notion that Japan had lost the war was immediately dismissed. In his world, it simply couldn’t have happened.

When planes flew over Lubang, dropping leaflets that urged him to come out of hiding, he thought it was a trap. Onoda’s brother even visited the island, using a loudspeaker to explain the war had ended. Unbeknownst to his brother, Hiroo Onoda was mere yards away, but again concluded it was a trap. In the decades that followed, Onoda would remain suspicious of any attempt to get him out into the open.

In fact, when he managed to get his hands on a Japanese newspaper, he saw a thriving economy. To him, it was evidence that the war situation had improved.

But by 1974, he was all alone on Lubang. Corporal Shimada had been killed in 1954 and Private First Class Kozuka was gunned down in 1972. Onoda resolved to keep holding out, but it would be an unexpected occurrence, initiated by a university dropout of all people, that would turn his world upside down.

Norio Suzuki had been traveling the world, and after having visited 50 countries, he chose Lubang as his next stop; specifically mentioning to his friends that he’d be looking for Onoda. One evening while Suzuki was building a fire to cook his dinner, Onoda appeared out of nowhere and threatened him.

In his shock, Suzuki managed to ask if he was Hiroo Onoda, to which Onoda confirmed he was. Suzuki explained to Onoda that the war had ended a long time ago and it was time to come home, but again suspicion reigned. One of Onoda’s army superiors, Major Taniguchi, had to be flown into Lubang Island to give Onoda his final orders to lay down his arms and cease military activities.

That was it. Hiroo Onoda’s almost 30 years on Lubang Island as a fighter for the Japanese Empire had come to an end.

Onoda returned to Japan in 1974 to a hero’s welcome. But despite his remarkable story, not everyone was enthusiastic about his track record. Onoda had killed innocent civilians on Lubang Island. And some people argue that he knew the war had ended in 1945, but chose to keep fighting anyway. It was salt to the wounds of those who’d lost loved ones when President Marcos of the Philippines pardoned Hiroo Onoda in 1974.

After some time, Hiroo Onoda’s shine started to wear off. Other veterans who had surrendered during the war were insulted when Onoda called them weak-willed. Their response was that at least they were smart enough to know when one of the largest wars in human history had ended. Also the new generation in Japan viewed Imperial Japan’s values as those which had brought destruction to the country. Celebrating Onoda would be celebrating those very same values.

Less than a year after returning to Japan, Hiroo Onoda left for Brazil, stating that people in the country no longer respected the ways of the past. He returned to Japan in 1984 and passed away in 2014, leaving behind a remarkable but controversial legacy.